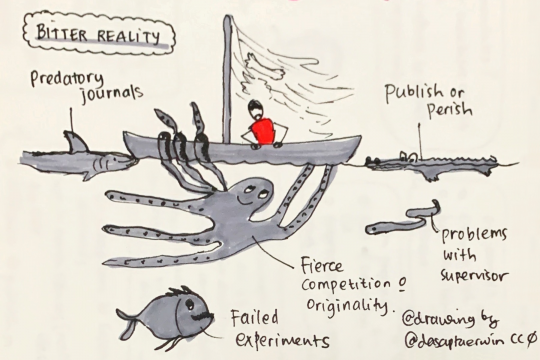

Did we publish in a predatory journal?

When I get a manuscript review request, I first look at the journal where the request comes from. More often than not, I do not know the journal's name. After all, perhaps 25000 scientific journals are published on our planet. If the request comes from a predatory journal, I mostly reject it. Sometimes I accept to expose myself to the nonsense deliberately (it's at the same time funny and frustrating). But how do you know whether a journal is predatory or not?

The question has been asked a lot over the last few years, e.g. in this Nature commentary. In the article, leading experts have come up with a definition.

Predatory publishers:

- prioritize self-interest at the expense of scholarship.

- are characterized by false or misleading information.

- deviate from best editorial and publication practices.

- lack transparency.

- use aggressive and indiscriminate solicitation practices.

However, the five criteria proposed by the above-linked article make me wonder. My question is: how many of these criteria need to be met by a publisher to qualify as predatory? And to what degree? The definition is too fuzzy to be helpful. A single criterion is not enough since even the top journals occasionally deviate from "best editorial and publication practises", which is one of the five criteria. The "lack of transparency" is perhaps as accurately describing many legitimate journals as predatory ones. Thus, 3 of the 5 criteria are also not sufficient. The Nature commentary mentioned above shows the dilemma of no criterium being sufficient and indicative on its own. There is even commercial help available in the form of curated lists of predatory versus legitimacy-verified journals. These lists are behind paywalls because if we eradicated predatory journals, these commercial offerings would also cease. Hence, they have an inherent conflict of interest and might too quickly place journals into the "predatory" category. Although I have used these lists, I did not find them especially helpful. It seems that the grey zone is much bigger than the graph of the Nature commentary suggests.

At the beginning of this year, some universities and entire countries started to blacklist some MDPI, Frontiers and Hindawi journals by putting them on an "X-rated" list (e.g. Norway). I was surprised that some science administrators want to blacklist all journals from these three publishers. This might be a bit exaggerated, especially considering the Frontier journals. I have both reviewed for and published in MPDI and the Frontiers journals, and I have reviewed for Hindawi. But recently, I have started increasingly rejecting review requests from journals that I cannot immediately place in the "legitimate" category because I do not have enough time to scrutinize each journal for its legitimacy and also do not have enough time for reviewing in general.

We have published one review article in Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology and two in MDPI journals (in Biology and in IJMS). And so have many of my very respected and highly legitimate scientist colleagues and friends. As an example, I can give the special issue Vascularization for regenerative medicine", which was guest edited by Andrea Banfi, Wolfgang Holnthoner, Mikaël M. Martino and Seppo Ylä-Herttuala. Enough said.

After publishing our review in the MDPI Journal "Biology", we can confirm that it is primarily up to the authors to maintain scientific integrity. The peer review was superficial, which is not what you want as a scientist. You want as much good criticism as possible to improve your manuscript.

On the other hand, both this and our Frontiers review were well received. The Frontiers review (Rauniyar et al. 2018) is ranking among the top 3% most viewed articles and has received 83 citations so far, which is an outstanding result, justifying the decision to write a dedicated review about VEGF-C. We noticed that in 2017, some people still cited the outdated 1999 review by Olofsson et al. in Current Biology. Also, the MDPI review from 2021 (Künnapuu et al.) has already gathered 18 citations. That is commendable, considering our niche topic: How protein diversity is generated within the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) family. Humans have only five VEGF genes, but we still generate more than 50 VEGF proteins from these genes (counting differences in the amino acid sequence as different proteins). However, you can see from the publicly available data that the time from first submission to final publication was hardly more than a month. That is a very short time for finding competent reviewers, reviewing the manuscript and resubmitting the improved version of the manuscript.

Frontiers, MDPI and Hindawi are operating for profit. They earn via the APC (article processing charges), which the authors pay to cover the expenses of what exactly? Peer review is free, the guest editors work for free, and a website is almost free*. Consequently, the more manuscripts the publisher accepts, the more money flows into the shareholders' pockets. But so what? That is also the case with traditional publishers. Money trumps the editorial and peer-review standards among predatory publishers, but it's a spectrum. And guess what? Hindawi has been owned since 2021 by John Wiley & Sons, with 1691 scientific journals the global number #4 in scientific publishing by journal number, after Springer Nature (3763 journals), Elsevier (2674 journals), Taylor & Francis (2912 journals), and followed by SAGE (1208 journals; numbers from here; but by article number Elsevier takes the #1 spot). And Frontiers is owned since 2013 (at least to a large extent) by the Holtzbrinck Publishing Group, which coincidentally also owns Springer Nature.

As long as universities judge a scientist's success based on how many research papers they publish, the problem of predatory publishers is unlikely to go away. The same is true for research misconduct: the still prevailing academic "publish or perish" culture encourages unethical practices among all players in the scientific arena.

Some of the lists that try to do the "predatory versus legitimate" decision for you:

- https://www.openacessjournal.com/blog/predatory-journals-list

- https://www.openacessjournal.com/blog/predatory-publishers

- https://beallslist.net (original list with un update from 2021)

- https://predatoryreports.org

- https://cabells.com (the commercial service)

And two sites that try to educate and document:

- Things to consider before submitting your manuscript for publication, including a check list: https://thinkchecksubmit.org

- It doesn't deal directly with predatory publishing, but there's enough of a connection to make Retraction Watch an interesting read. Just another consequence of the way we do science.

*Admittedly, long-term preservation of electronic data costs money, but these publishers have no track record yet to judge them.